Seeing Documentary as Participatory Art. (Summary of work in progress)

This research with the Department of Film and Screen Media at University College Cork is funded by the Irish Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship scheme. https://research.ie/funding/goipg/

This research takes as a starting point the illusion of completely ethical participation of subjects in documentary film. Experiments in the participation of human subjects in the production of a documentary film promised to address some issues relating to authorial projection and editorial control. This page is a journal/ scrapbook of various methods that have been used in film and contemporary art to attempt to address these issues.

Cinéma Vérité

The term Cinéma Vérité was coined by visual anthropologist Jean Rouch and philosopher Edgar Morin for the 1961 film Chronique d'un été. The film follows a group of young Parisians as they investigate their own lives and that of others using relatively new portable film and audio technology. Notably it also includes a 'feedback' session, where participants were screened the rushes of the film, and then filmed as they commented on them and discussed their feelings about how they were represented. This film was an early experiment in participation and a reaction to the elaborate artifice that was associated with American cinema.

This early experiment in participatory documentary was flawed, but set a precedent for other such experiments, and laid the groundwork for a genre of observational documentary filmmaking.

The Myth of Total Cinema

André Bazin wrote in 1967 (What is Cinema? Vol. 1) about the objective potential of cinema (film). From its inception it promised that it could faithfully represent reality, but that this dream is not realisable. Cinema has not yet been invented.*

Film is therefore a language, not a reflection of phenomenological experience. Editing decisions can directly shape the experience of the viewer (as happened in Chronique d'un été), and so the ultimate control lies with the filmmakers, often intentionally or not.

*Bazin, André. What Is Cinema? Volume One. Translated by Hugh Grey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

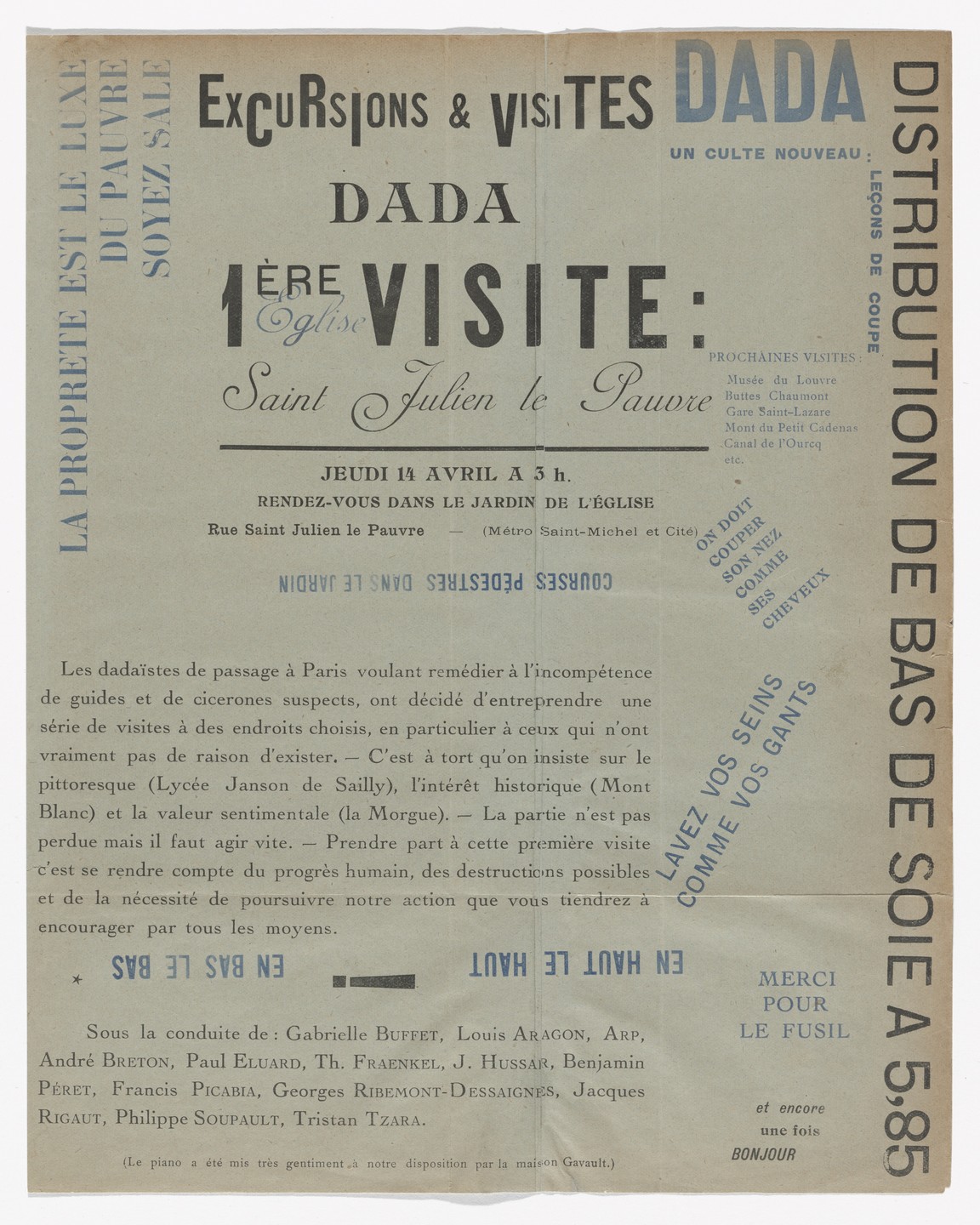

Excursions et Visites. Jeudi 14 Avril, 1921.

One of the first known experiments with (what is now called) participatory art took place in 1921 in Paris, organised by Dada artists André Breton, Tristan Tzara and others. The event was titled: Excursions et Visites and was a type of absurd and nonsensical guided tour of Paris, beginning at the churchyard of Saint Julien le Pauvre. It was a failure, it rained, and nobody turned up (many of us artists can relate to this). The intention, however was to create a public artwork, where the 'audience' became more than spectators, but active participants in the work.

For these Dada artists, this was an assault on the cultural establishment of the time, exploding the relationship between artwork, artist and audience. Though mostly a failure, the event created an opportunity for public participation in artworks as avant-garde practice, "... a re-evaluation of everyday objects and experiences as a point of opposition to cultural hierarchy."*

*Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso, 2012.

Enough Mystifications

If there is a social preoccupation in today’s art, then it must take into account this very social reality: the viewer.

To the best of our abilities we want to free the viewer from his apathetic dependence that makes him passively accept, not only what one imposes on him as art, but a whole system of life . . .

We want to interest the viewer, to reduce his inhibitions, to relax him. We want to make him participate.

We want to place him in a situation that he triggers and transforms. We want him to be conscious of his participation.

We want him to aim towards an interaction with other viewers.

We want to develop in the viewer a strength of perception and action. A viewer conscious of his power of action, and tired of so many abuses and mystifications, will be able to make his own ‘revolution in art’.*

*GRAV, ‘Assez des mystifications’, in Caramel (ed.), Groupe de recherche d’art visuel 1960–1968

Ethnofiction, metafiction, parafiction

Jean Rouch developed a method of visual ethnography using portable 16mm cameras and sound recording equipment. His aim was to somehow faithfully represent the cultures that he engaged with. He quickly realised that simple observation was flawed- the camera is always present, and (as was pointed out by participants in Chronique d'un été) the person in front of the camera will always be aware of this presence. His experimental solution was to embrace the position of the camera in the situation, and to hand some of the narrative control over to the subjects in the film, making them participants. Moi, un noir (1958) is an example of this. The film depicts migrant workers in Nigeria who recreate scenes from their own lives, under different names. The term ethnofiction is used to describe the film. This new form embraced the impossibility of objectivity in documentary, instead combining the points of view of the viewer, participant and filmmaker to deliver a subjective narrative that is perhaps as close to the truth as can be possible.

An earlier (and perhaps the first) ethnofiction was Les Maîtres Fous (1955). Styled more like a conventional ethnography, this film shows rituals of the Hauka movement in Niger, who are shown as being possessed by the spirits of former colonial masters. The beauty of this film for me is summed up by this reaction to it by Amy from The Movie Checklist youtube channel, who is horrified that she really cannot find a genre to attach to it (she does mention 'mocumentary' at one point...).

This is a key point for me. Rouch's ethnofictions deftly avoid conventional genre classifications. To approach watching Les Maîtres Fous or Moi, un noir as documentary or fiction, or mockumentary is to mis-read the message.

History, Demonstration, Participation

Perhaps the biggest challenge for documentary film is the recounting of historical narratives in a way that reflects the influence on these narrative by power and ideology. Artist Jeremy Deller recognised early in his career that perhaps the best way to tell a story about the past is to have it interpreted by others, perhaps those same others that might end up watching a documentary.

In his 2001 project, The Battle of Orgreave Deller recreated a battle between striking miners and police that took place in 1984, enlisting the help of many former miners who were present at the original battle. Similar to the original aims of Chronique d'un été, Deller gave up much of his control of the project to the participants. This documentary film was made about the project by Mike Figgis. In the selected clip, Deller explains his feelings about how the recreation is working:

...and here in a conversation with London College of Communication's Simon Hinde, Deller expands on his feelings about his work of art going out of control:

The great thing about this project, and the documentary, is that it does what so many works of contemporary art fail to do: it transcends the act and the work of art itself. As I write there are 106 comments on Youtube about the film, and for the most part they are comments on the political landscape in the late 80's in the UK, and about the contemporary implications of this event. This is art as a place for debate, the dream that Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin had for Chronique d'un été.

Ausländer raus!

All types participation do not seem to be equal. In The Battle of Orgreave a lot of the control was given up to the participants. They took ownership of the project, as they should- it was their story that was being re-told, and they all felt like it was important that the story was told from their perspective. This is close to what Jacques Rancière would call Genuine Participation; the invention of an unpredictable subject who momentarily occupies the town square or the factory. The key point here is that the ultimate power lies in the hands of the participant. In The Battle of Orgreave the power ultimately was handed over mid-way though the process. My understanding of The Battle of Orgreave and Deller's project comes from the film by Mike Figgis, whose sympathetic point of view brought us the project as a documentary. The separation here is between the work of participatory art (the project) and the documentation of that project (the film), which was not a work of participation.

Ausländer raus! was a 2001 project by Christoph Schlingensief. In response to the election of a

number of members of the ultra right-wing party Freedom for Austria to parliament, Schlingensief set up a 'concentration camp' made from shipping containers in the centre of Vienna for one week, and housed a number of asylum seekers inside. Video of the inside of the camp was streamed live on the internet, and visitors to the website could vote to have a pair of asylum seekers deported each day. A large banner on top of the containers read: Ausländer raus! (Foreigners out!).

The piece attracted huge attention, both on the square during the duration of the project, and also on national media. Most of all, it sparked debate, and in the film made by Paul Poet, Ausländer Raus! Schlingensiefs Container we see Schlingensief himself on a platform actively and often aggressively provoking the crowd with a loud-speaker.

If the aim of Ausländer raus! was to provoke a debate about the current political attitude towards immigrants in Europe, and to expose the latent xenophobia in ordinary people, then it succeeded. Passers-by rant and argue, the camp is raided by a band of ‘hippie’ liberators and attacked by firebombs. The experiment spiralled almost to the point of going out of control. If we take this as a positive attribute of a work of participatory art, then it worked. However the ‘asylum seekers’ themselves at the centre of the project have no voice in the film, or in the work itself it seems. As a work of politically provocative participatory art, or a social experiment where the objective was to prove that there are inequalities in a society it works. Schlingensief had a message that he wanted to deliver, and he was confident that the potential participants is his project would do his bidding (and they did).

If we contrast this to Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave we can see that Deller did not seem to have a prescribed message, rather the objective of the participatory element to his work was to write its own message. It comes down once again to power, in this case the power of the message, the voice: to whom does it belong? What message will it carry?

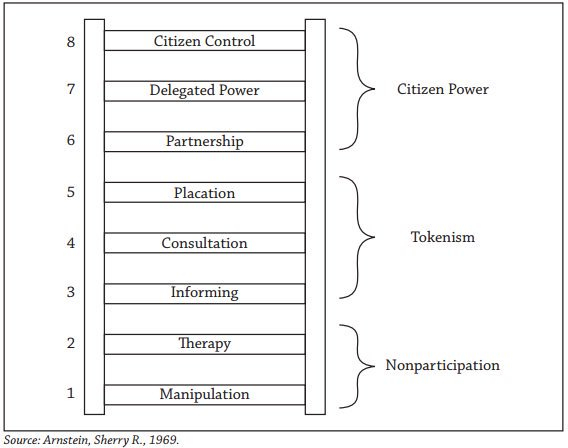

‘The Ladder of Participation’, from the Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 1969

Everybody in the Place

Power, then is at the centre of discourse around participatory art projects, just as it is with states. A work of art, or a documentary film that has a group of people as a subject or at the centre has two possible extremes- it can be a dictatorship, an oligarchy or a democracy. In most cases the artist dictates the terms of the work, they might work with a gallery, museum or commissioning body to decide the direction of a work, but it is generally accepted that the artist is the centre of the genesis of a project. The myth of the artist-genius seems to be just as relevant today as it was in the Renaissance or in Warhol’s Factory.

So what does it mean to relinquish control of an artwork to the very factors that it is comprised of? For the sake of example or argument we can rule out the human factor. In conversations with David Sylvester between 1962 and 1974, Francis Bacon often refers to his method of painting to be governed by ‘luck’ and ‘accident’.* He explains that he simply spends his time confidently lashing paint on to the canvas, beginning with one idea, and eventually something might happen. This can be read in a couple of different ways. One is that Francis Bacon was a creative genius, all he had to do was work away and eventually a very important work of art would emerge. The other is that he simply was not in full control of his process, that he certainly had a part to play, but other external factors, perhaps his environment, his state of mind, the weather or the company he was keeping were participating in the creation of the painting. If we re-introduce the human factor to a work of art, such as a documentary film about a group of people, and apply the idea that the artist/ director is ethically bound to hand over some or all of the control of the project to the participants/subjects. Now we are talking about microcosmic political decisions, but ultimately the question is about who (or what) has the power over the message. This is difficult, especially when dealing with a large amount of people. Experiments in communism (communism as in the act of living, working and making decisions communally) in the 1960’s and 1970’s have shown that it is productively cumbersome to have large groups making decisions. And perhaps when it comes to a creative work, the initial intentions and impact might become diluted. Rouch and Morin seemed to have realised this during the production of Chronique d'un été. The premise of the experiment is presented as intact, but in fact the film was heavily edited in order to deliver the message effectively and artfully.

*Sylvester, David. Interviews with Francis Bacon. 1975.

Antagonism

A recent project by Jeremy Deller takes a fairly unique approach to this issue of a balance between the delivery of an effective and engaging message and the factor of unpredictability that comes with participation. Everybody in the Place (2019) is a project about the history and contextual relevance of rave culture in the 1990’s UK. Deller begins this project in a fairly conventional manner by creating a (very interesting) didactic presentation. The unpredictability factor comes in as he presents his essayistic lecture to a group of secondary-school students at a school in inner-London. The lecture was filmed and this became a new version of events. His ideas, his research and his version of the history and impact of rave culture was mediated by a group of people, most of whom were not born at the time. In this project, Deller is actively seeking to have his own ideas and opinions challenged, and this becomes the ‘documentary’. If we were to use Armstein's Ladder of Participation above to categorise this approach, we might call it 'delegation of power'.

Deller actively invites his participants (the class) to challenge his presentation, perhaps in recognition of the fact that his own perspective may be tainted by nostalgia and personal experience. Rave culture here is presented back in a contemporary context that seems to be a lifetime away from its heyday. Claire Bishop identified this type of Antagonism as a crucial missing factor in the practices of Relational Aesthetics*. The function of Antagonism in a participatory artwork is to detach the artist from the work. The presence of the 'other' (in this case the students, born a generation after UK rave culture) prevents the artist from being too firm in her own identity and beliefs. She becomes vulnerable to criticism, and the message remains subjective. Deller is noticeably surprised by some of the comments that he receives in Everybody in the Place, but he seems to handle them well. A question must be asked about the editing of the film, are more awkward moments omitted? Presumably, and if so we return to the same problem we were faced by when considering Chronique d'un été: it is a filmic representation of a work of participatory or dialogic art where the participants seem to have agency in the creation of the scenario or the situation. But then rushes are then taken away and edited, so what the public ultimately gets to see is the filmmaker's version of events, however biased that might be. In Deller's film, there is one redeeming factor. The 'narrative' of the film is based on his Powerpoint presentation, and so radical temporal editing is difficult.

*Bishop, Claire. 2004. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October 110: 51–79.

The idea of Antagonism as a crucial constituent element to a dialogic artwork was taken by Claire Bishop from theories on democracy by Enesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Her criticism of practices of Relational Aesthetics as described by Nicolas Bourriaud is that they rely too neatly in ideas of communal togetherness and common values. Antagonism, is not what Christoph Schlingensief achieved in Ausländer raus!. In that case its overpowering provocations of violence and conflict turned it into a lost opportunity to create a space for genuine discussion.

Divesting Ideology with Dialogics

Nicht ohne Risiko (2004) by Harun Farocki (Trans. Not Without Risk, or Nothing Ventured)

A look at Harun Farocki's documentary about an investment negotiation provides a way of understanding the effects of simple observation. The film documents a drawn-out conversation between two investment bank employees and the founders of a start-up company over the terms of investment. It follows every (almost boring) gesture of this negotiation to the point where the language of capitalism itself is separated from the narrative. Jan Verwoert identifies how the film reveals the systems of power that lie within through this methodology of 'deadpan documentation'*. The film's antagonisms lie between the relationship of the filmmaker to the participants, and between the participants and the audience. Presumably the participants were provided with full information about the process, researched the artist's previous work and provided consent, even though they may have been aware of the critical nature of Farocki's work. The consent provided in this case adds to the flavour of the effect- ideology that is unashamed.

* Verwoert, Jan. 2005. “Production Pattern Associations On the Work of Harun Farocki.” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 11: 64–78.

Dialogue here forms the content and substance of the film- it is the means by which the message is achieved in terms of the disclosure and divestment of ideology. Farocki's method here is based in an understanding between himself and the participants- they provide the dialogue, the performance, and he documents. There is no question after watching Nicht ohne Risiko that however the films claims to be objective documentation on the surface, the participants, being aware of the camera, the filmmaker and the viewers are placed in the inevitable position of performers. They perform their own roles as negotiators, as they would in private, but also they perform as the images of themselves and their ideological convictions. The film becomes self-reflexive.

Solidarity

As part of her research for her 2019 film Solidarity, artist Lucy Parker Lucy Parker filmed a conversation between four men and herself. The men were all victims of workplace blacklisting because of their associations with union activism. The four men sit around sipping beer in a pub, discussing the effects that the blacklisting has had on personal lives. Parker sits with them, asking questions, and sometimes focusing in on aspects of what they say.

The short film seems to take the form of a conversation, though again the men would have been very obvious of the presence of the cameras, microphones and the artist. The position of the artist at the table with the men marks a difference. This film does not pretend in any way to be an objective observation of a conversation. The artist is not here a participant- she has a defined role as moderator, listener. But it is not an interview. Here the men are in direct dialogue with an audience, and the artist is a medium. They share personal stories in front of this audience because they want their stories to be heard. This is the contract that parker has made with the men: they sit and talk openly in her company, she provides an audience. This is truly a collaboration, as well as an observation on group dynamics.

Editing is again brought in to question in this work by Lucy Parker. It seems that two cameras are being operated. It is obvious, especially in some of the images made outside of the pub, that the sound is being synced over various images, perhaps for the sake of continuity. But the overall impression is that the artist has an agreement with the participants, she is in dialogue with them and their intentions.

This film makes up some of the research that Lucy Parker made for her film on the same topic, Solidarity, which is a more conventional documentary with interviews, footage taken from a 'town hall' meeting, archival footage etc. The intention behind the publishing of this discursive research element must also be noted. In this case it seems to be a statement of intention by the artist to participate openly.

Island

Steven Eastwood's 2018 documentary can be seen as an example of a project that does not set out to be a work of participation, or dialogic, but almost inadvertently becomes so. The film is an observational account of the experiences of four terminally-ill individuals as they are taken care of in a hospice. Speaking at a masterclass he gave at University College Cork in 2019, Steven Eastwood described how he wanted to break the taboo of showing the death of a person on film, and that this objective was the beginning of his process in this case. Throughout the film, the viewer encounters very intimate encounters with each of these individuals. The camera often appears to be static, as if abandoned, as the people in front have appeared to have forgotten its presence. In other scenes it is obvious that the filmmaker and the individual are the only ones present. The participants speak directly to the camera, or rather directly to the filmmaker, and he replies, disclosing his presence. In other scenes, the filmmaker is seen briefly, like in one scene where he holds a cigarette as Alan, one of the participants, smokes.

What is interesting here is that many of these moments where the filmmaker becomes a part of the scene are included in the edit. It is as if by adding these scenes, the filmmaker is describing his personal relationship with the participants. They address his by his first name, and often talk to him as if he were a friend. Close to the end of the film, one of the participants, Alan, dies on camera. When this happens we hear Steven being woken by a nurse: "Steven, Alan's gone..." And then he asks to sit with him for a while.

What seems to have happened is that this project started out to be a conventional observational documentary, but by virtue of the personal relationships that developed between Steven and the participants it became a work driven primarily by participation and dialogue. the filmmaker is ethically obliged to move between the camera and the subject.

Added to this is the attitude of the participants. They seem to have the attitude that they have nothing to lose, and so the film takes on a tone of irreverence. A cultural taboo is broke, that is openly discussing and observing death, and the participants take full control of this element of the film, in fact they seem to be pleased to be able to expose their deteriorations. Here lies the antagonism. By allowing these people to show the process of dying, they challenge the harmony embedded in other documentaries that might simply confirm ideological beliefs.

***A forthcoming interview with the filmmaker will reveal more details about his intentions***